Presses

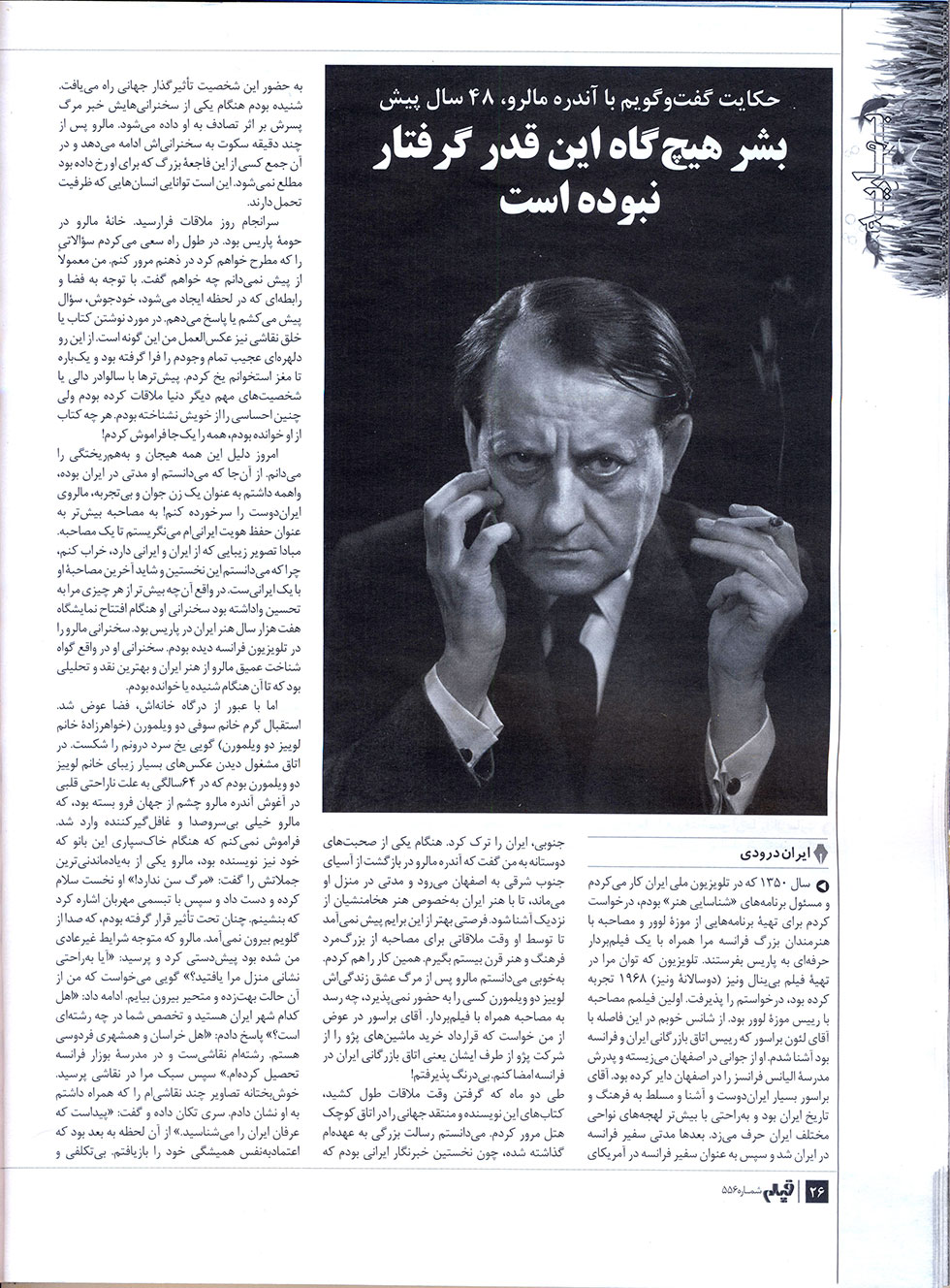

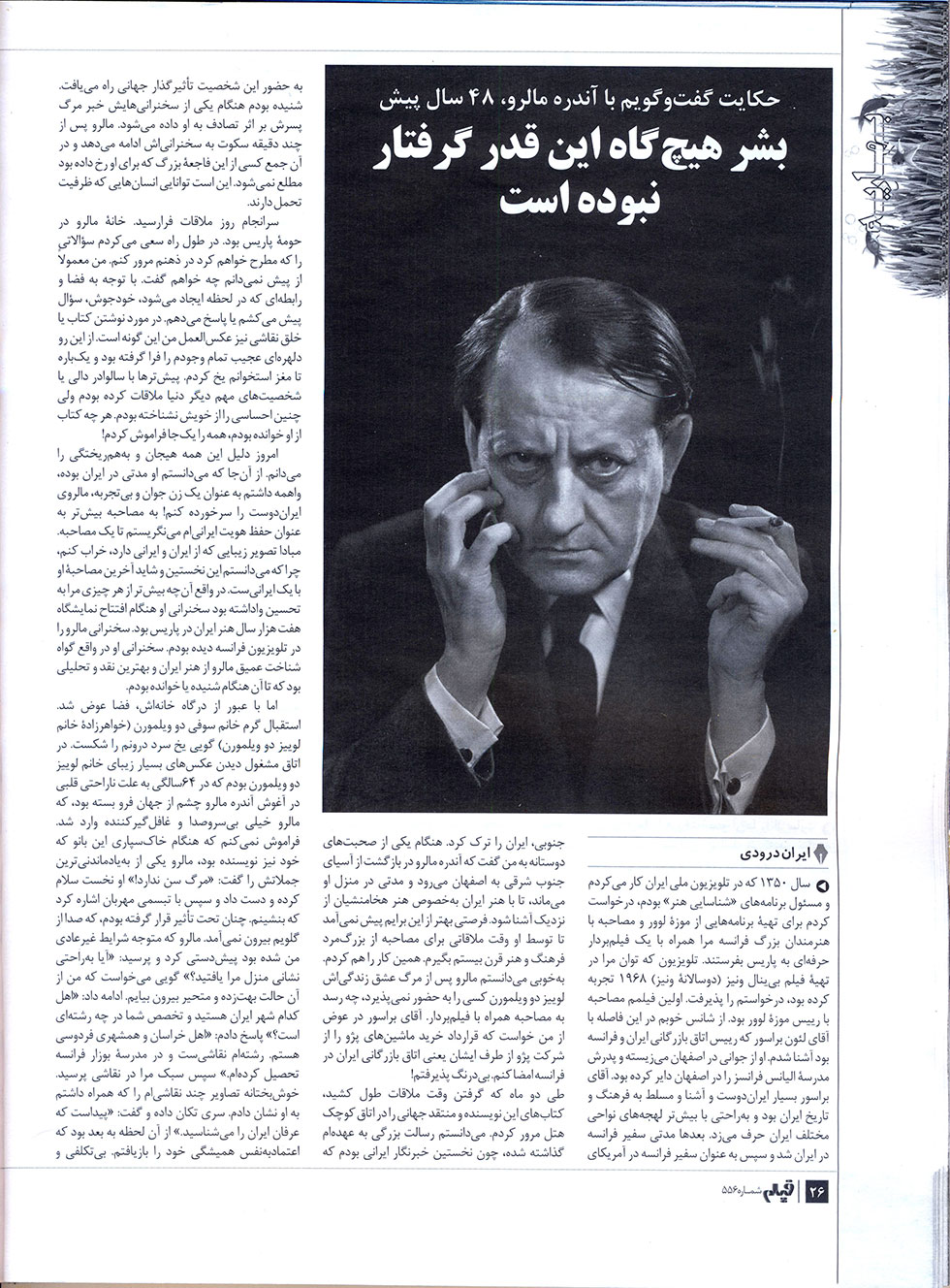

The story of my interview with Andre Malraux, in 1971

The story of my interview with Andre Malraux, in 1971

In 1971, I was working as an art program producer in Iran’s National Television (INT), when I asked the management to send me and a professional cameraman to Paris to produce a set of programs about The Louvre museum and hold a few interviews with French artists. Considering my background and production of a Biennale Venice Film in 1968, the INT management agreed with my proposal. The first part of the plan was to conduct an interview with the director of The Louvre museum. While staying in Paris, I had a chance to get acquainted with Mr. Leon Brasseur the head of Iran-France Chamber of Commerce. He had lived in Isfahan in his youth and his father was the founder of the Alliance Frances School in Isfahan. Leon Brasseur loved Iran very much and was completely familiar with Iran’s culture and history. He spoke comfortably in most of the regional dialects of Iran. Later he was for a while the French ambassador to Iran, before he was appointed as the French ambassador to South America. During our friendly exchanges, he mentioned that Mr. Malraux intended to stay at his house in Isfahan on his way back from India, stating that Mr. Malraux was keen to study Achaemenid Iranian art close-up. That was a unique opportunity to arrange an interview with the prominent champion of twentieth century culture and arts. I was aware that it was really difficult to have an interview with Malraux who had not accepted anyone’s request after the death of Lewis de Vilmorin. In return Mr. Brasseur asked me to sign on his behalf (i.e. Iran Chamber of Commerce) the contract to buy Peugeot cars. I accepted it instantly.

The process of securing this meeting took two months. During this time, I had the opportunity to study and review all the books written by this acknowledged author in my small hotel room. Since I was the first Iranian reporter who had the honor of meeting this noble figure, I knew it was a great mission entrusted to me. I had heard that he received the news of his son’s death in a car accident while he was in the middle of a speech. Malraux managed to continue his talk just after a few minutes of silence and his audience didn’t hear about the horrific news. This is the ability of some people to show patience and endure suffering.

Finally, the wait was over. Malraux’s house was in the suburbs of Paris. On my way, I reviewed all my questions, trying to choose the best ones, but unfortunately during the interview I could not remember my list of questions or even read my notes. Actually, I don’t usually know what I am going to say in advance. I answer and ask questions on the fly, effectively based on the evolving interactions during a conversation. My approach is the same when I am writing a book or creating a painting. But that day, I was nervous and I froze. I had had previous meetings with Salvador Dali and other international celebrities, but had never felt like that before. I forgot everything I had read and tried to memorize before this meeting.

Now, in retrospect, I realize the reason for all my anxiety. Malraux had been in Iran for a while and as an inexperienced young Iranian woman, I was afraid of disappointing him! So I regarded the interview not merely as an interview but an effort to preserve the Iranian identity and reputation. I was afraid of damaging the beautiful picture of Iran that he had in his mind. This was particularly because I knew that my interview with him was the first, and probably also his last interview with an Iranian reporter. In fact what made me admire him even more was his opening speech in exhibition of “7000 Years of Iranian Art”. I was not invited to that event but watched on television in Paris. His speech not only was clear proof of his deep knowledge about Iranian art, but it was also the best review and analysis I had ever heard or read.

But as soon as I walked in, the atmosphere changed completely. The warm greeting by Ms. Sophie de Vilmorin (Ms. Lewis de Vilmorin’ niece) broke the ice. I was looking at pictures of the late Ms. Lewis de Vilmorin who passed aged 64 from heart disease when Andre Malraux entered the room quietly. I never forget one of the most memorable sentences by Malraux at her funeral: “Death has no age!” He greeted me and offered a seat with a warm smile. I was so impressed but at the same time felt speechless. Malraux, who had sensed my anxiety, in a preemptive gesture asked: Did you find my address easily? And continued with further questions; which town are you coming from and what is your profession? I replied: I am from Khorasan, like Firdausi, and my field of work is painting. I studied in Beaux-arts, France. Then, he asked about my painting style. Fortunately, I had a few samples of my works with me, which I showed him. He shook his head and said: it shows you are familiar with Iranian mysticism. It was at that point that I recovered my confidence. His humble attitude helped me to think about my questions. Sitting against me was an imminent international personality and at only 31, I had dared to say: “I am a painter too!” And so, the interview started with my first question.

Malraux is as humble as he is creative. At the end of interview I felt elevated to a new stage in life, as though somehow meeting with this exceptional person was a big boost to my soul. I will never forget that during the interview Malraux tried to explain everything at a level that I could appreciate them and avoided overwhelming me with his superior knowledge. Such behavior added to my respect and admiration even more. That was the reason behind asking him a private question towards the end of meeting. I asked my cameraman to keep on filming and taking more photos. My question was: How do you see me as a woman? His smile turned to laughter, his reply was brief: “a very interesting woman”. I leaned towards him and said, “Your answer is proof and I will be sure to tell my husband that you think that!” At this time he looked at me surprisingly and asked me: Were you in doubt? My answer was: I know I’m an intelligent person, but I don’t know what kind of a woman I am. At this point he asked for a piece of paper to write me a note. I read his note in the taxi on the way back to hotel: “Try to make people recognize their inherent greatness.” I remembered this was the title of a chapter of his most popular book “Human Conditions.” At that point, I received a precious personal endorsement from the world’s greatest critique and writer. Before leaving, he said in a commanding tone “Remember, you can publish the interview only after my death.” And I did. Several years later in 1976 I handed it over to a very reputable French magazine, Le Point. Such a request was amazing for the magazine editor since there was not much published about Malraux after his death. After a few minutes of silence, the editor asserted: This is one of the most concise and beautiful interviews of Malraux that I have ever seen. As if they have compressed all of Malraux’s interviews into one. Maybe he wanted his best interview to be published after his death.

I am writing this article 49 years after I met with Mr. Malraux. I ask myself, would it have been possible to imagine these days back then, and know how proud I would feel remembering such memories? At the age of 82, on the eve of the New Year,

I say to myself: Important values could only be achieved if they have been recognized first.